Security is everyone’s responsibility. How is that supposed to work? Our teams have struggled for a long time trying to move away from reactive work to planning and building for a more resilient future.

Is that shift even possible given our small teams and the never ending stream of issues to respond to? How can you scale your security practice in any meaningful way?

Security issues are often deeply technical and nuanced. Delegating work is a constant challenge and it feels like we’re explaining the same things over and over again. Security teams are stuck.

In this talk, we’ll dive deeper in the roles security teams play within most organizations. We’ll explore the common approaches to running a security practice, what works and what doesn’t.

Then, we’ll start to examine communication techniques that can have a positive impact. We’ll look at how you can shift your work from constant response to more impactful efforts by laying the groundwork for others to succeed.

You’ll walk away with a better understanding of the problem your team is facing and some small steps you can take now to enable other people with your organization to make better security decisions.

You are a dedicated security professional. You understand your area of expertise deeply and are working the best you can to help improve the security of your organization.

You're working on a team of like-minded individuals. While it can be challenging always facing threats and trying to help reduce risk, you generally work well together.

The challenge is that your team is accountable for the security of the organization.

But you work with a lot of teams in the rest of the business. Those teams are responsible for various business goals. They are working just as hard to meet those goals.

It can be hard to keep up.

Why is it hard to keep up?

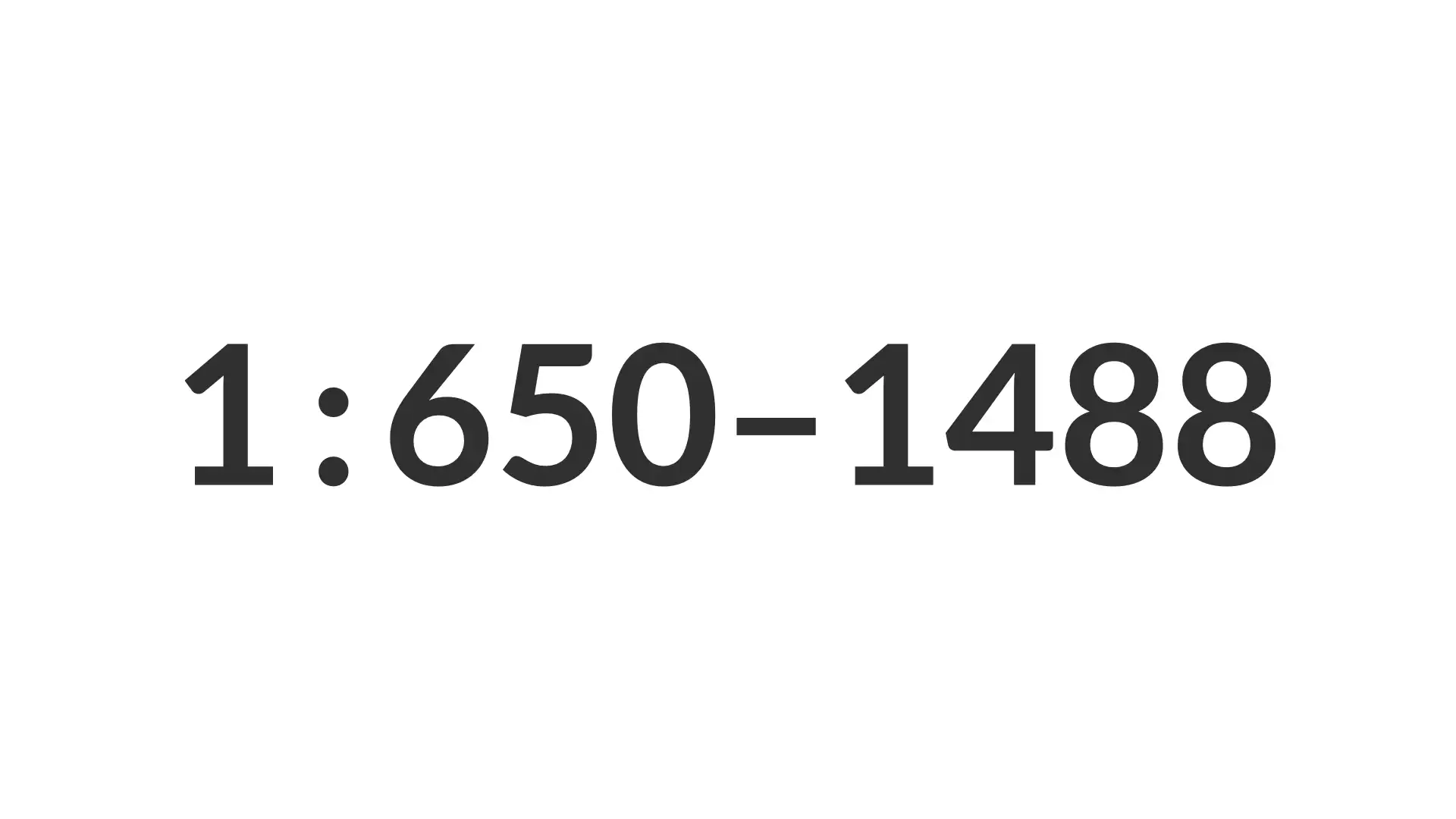

A few years ago, a couple of different analyst firms looked at the ratios of security professionals to the rest of the business.

They found that there was about one full-time security resource for anywhere from 650 to 1,488 other employees.

That's one person responsible for the tools, processes, and output of at least 650 others. Is that even possible?

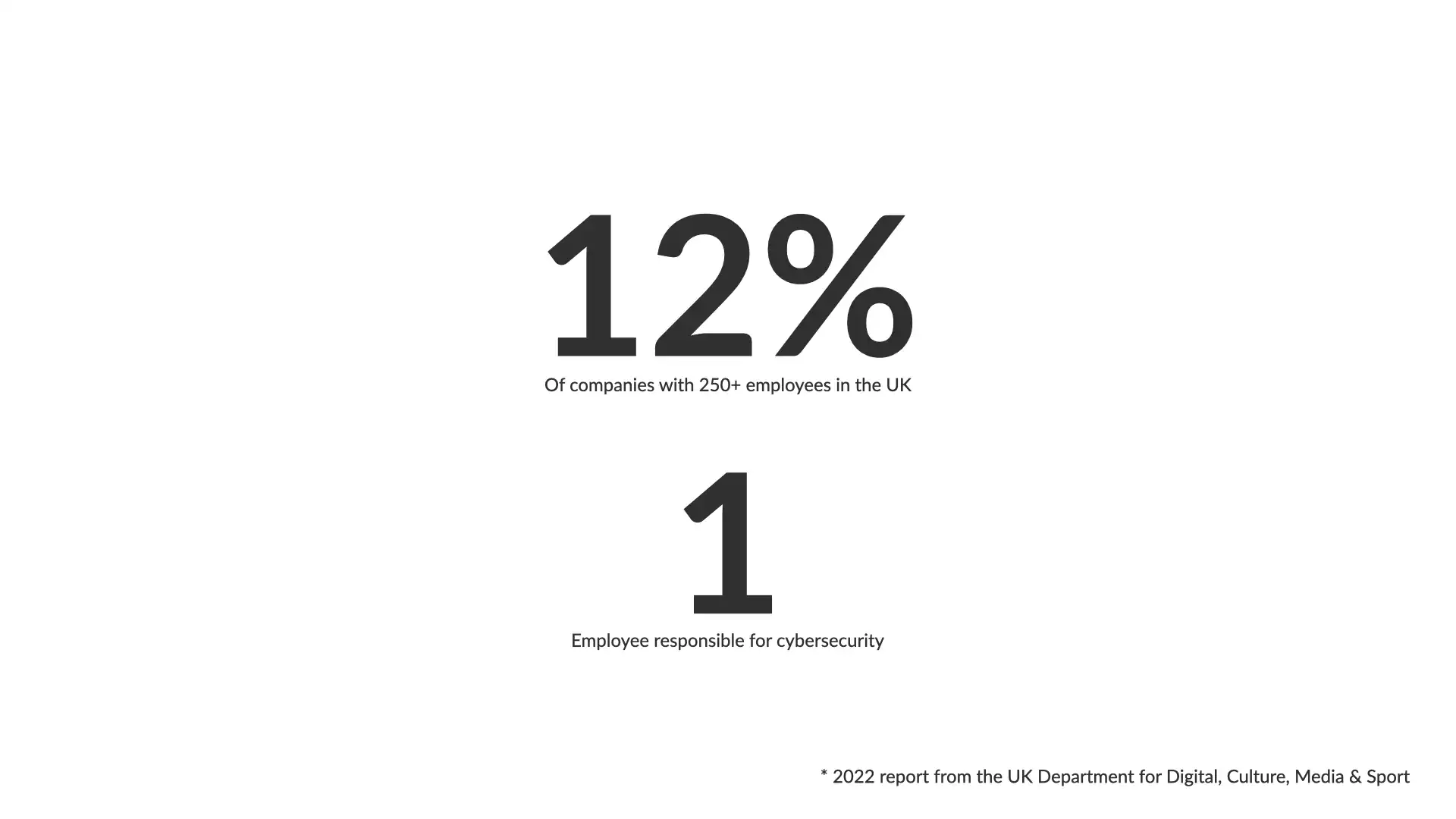

In 2022, a report from the UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport provided a similar metric.

They found that 12% of businesses with 250+ employees had 1 person responsible for cybersecurity...and that wasn't necessarily a full-time assignment.

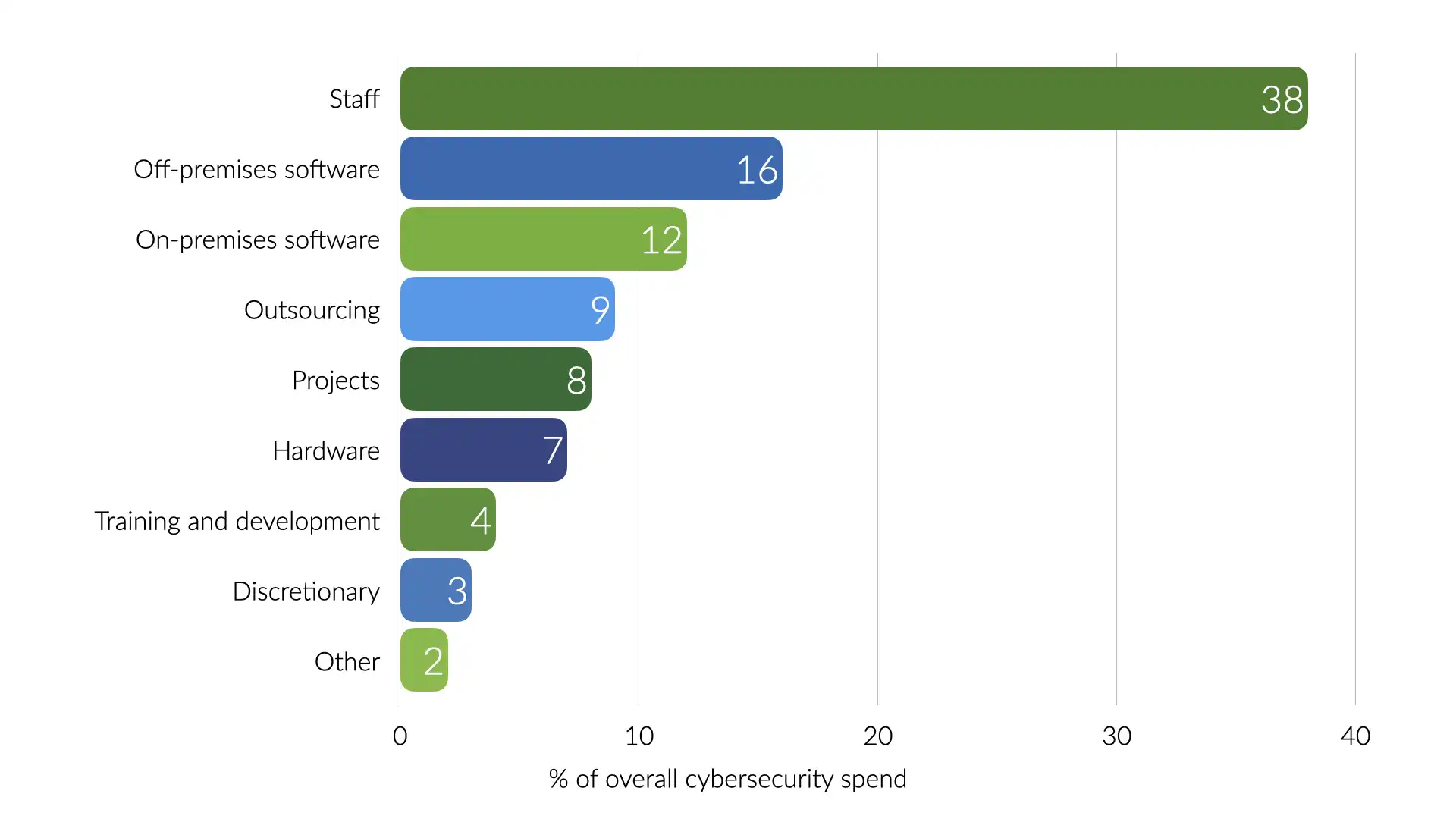

In 2023, Venture Beat conducted a survey and found that most organizations spend just shy of 10% of their IT budget on cybersecurity.

38% of that spend was on staff. That works out to 3.8% of the overall IT budget spend on security personnel.

That sounds like a lot, but there are some of the most highly compensated individuals on staff. Good for those in the industry, still representative of a disproportionate ratio of security folks to the rest of the business.

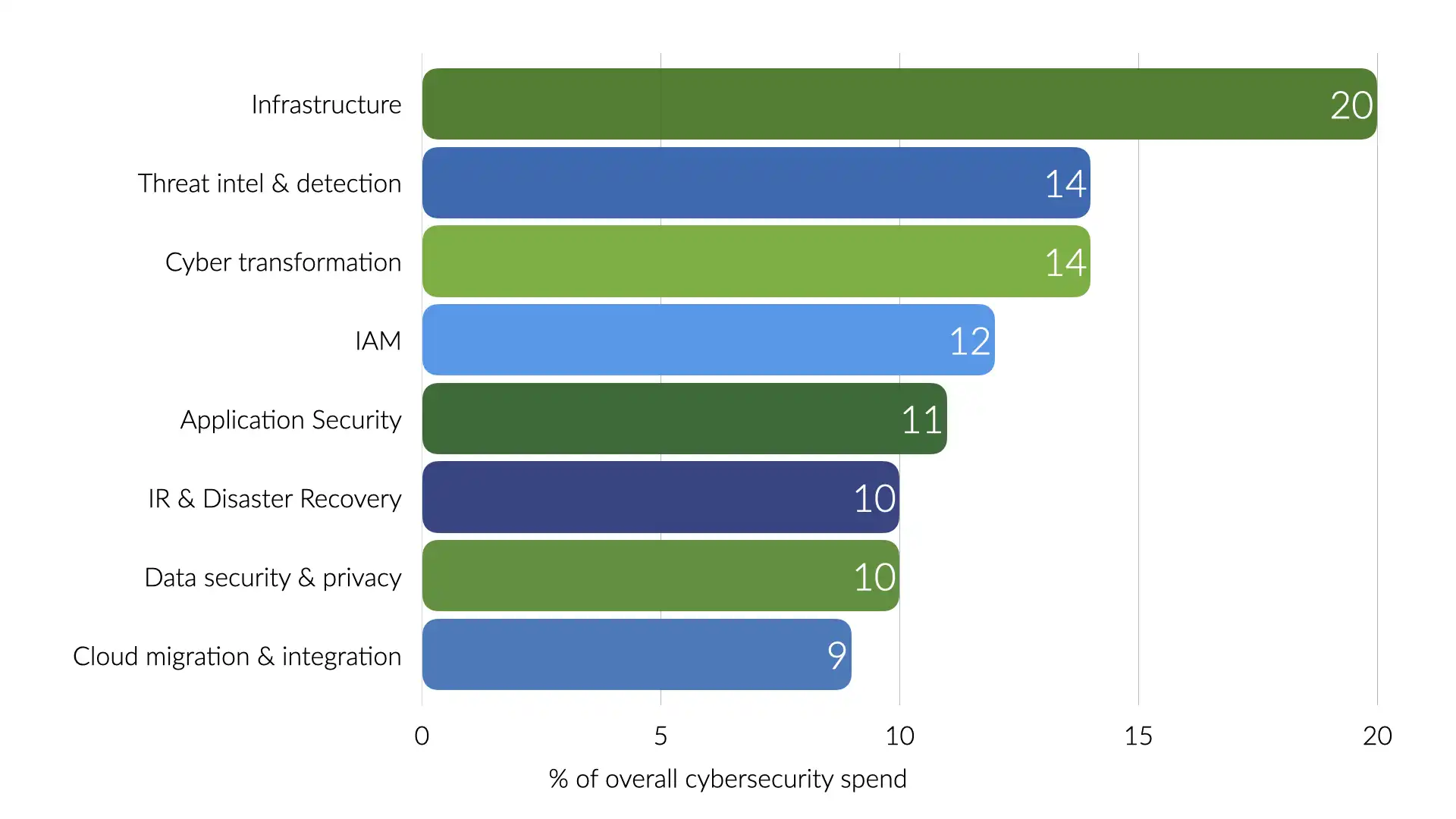

The Venture Beat survey provides even more insights. Most of the security spending is going to infrastructure and threat intelligence and detection.

That loosely translates into outer perimeter controls and figuring out what's already causing issues within your systems. Very little directly into scaling up the security team or preventing security issues in the first place.

The result of all of this is a lot of security folks feeling burnt out. Security teams are overworked, constantly fighting fires and trying to answer why a significant chunk of the IT budget is being spent on simply not losing ground.

We should do better. Can we?

Organizational design

...or lack there of

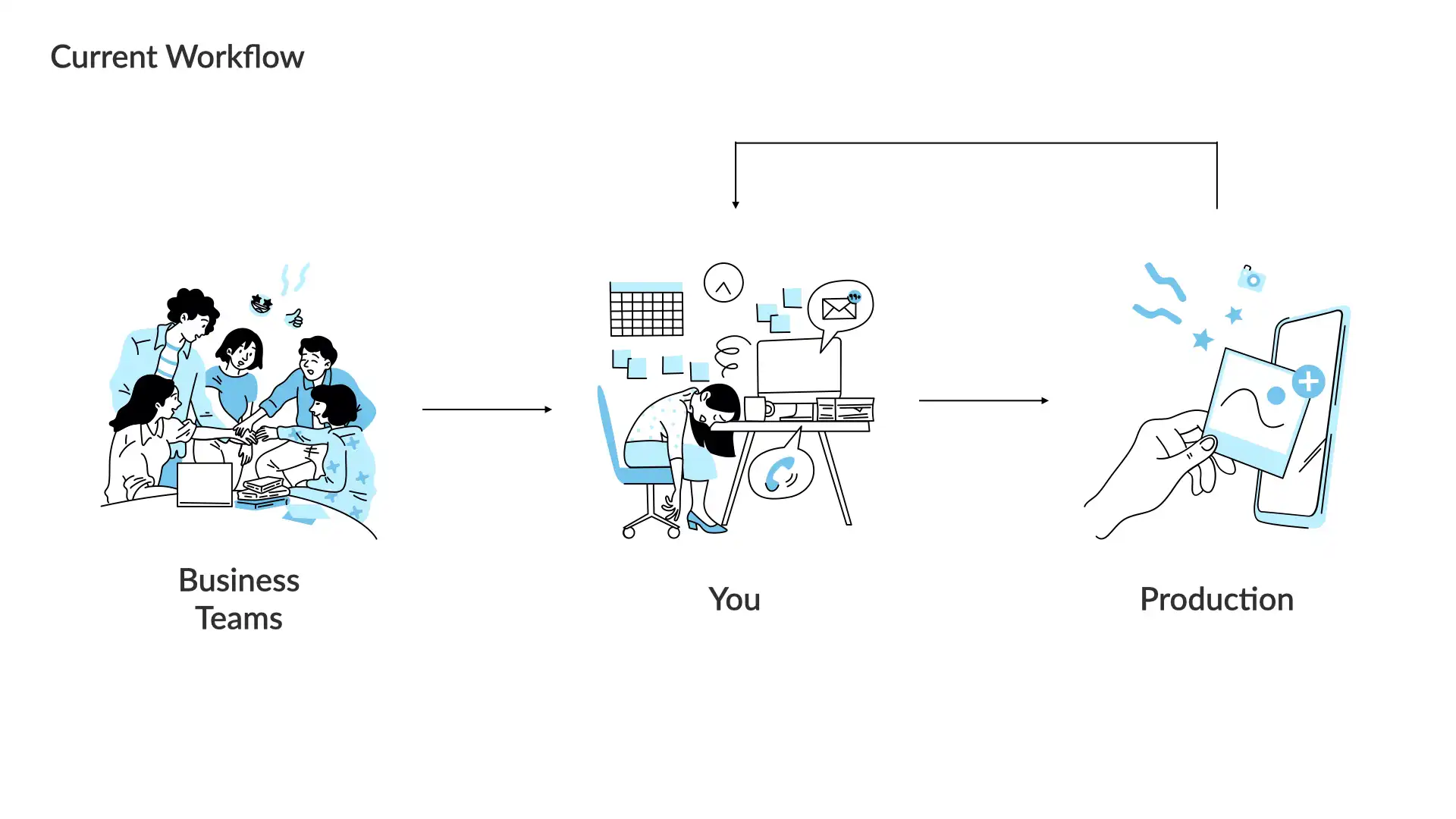

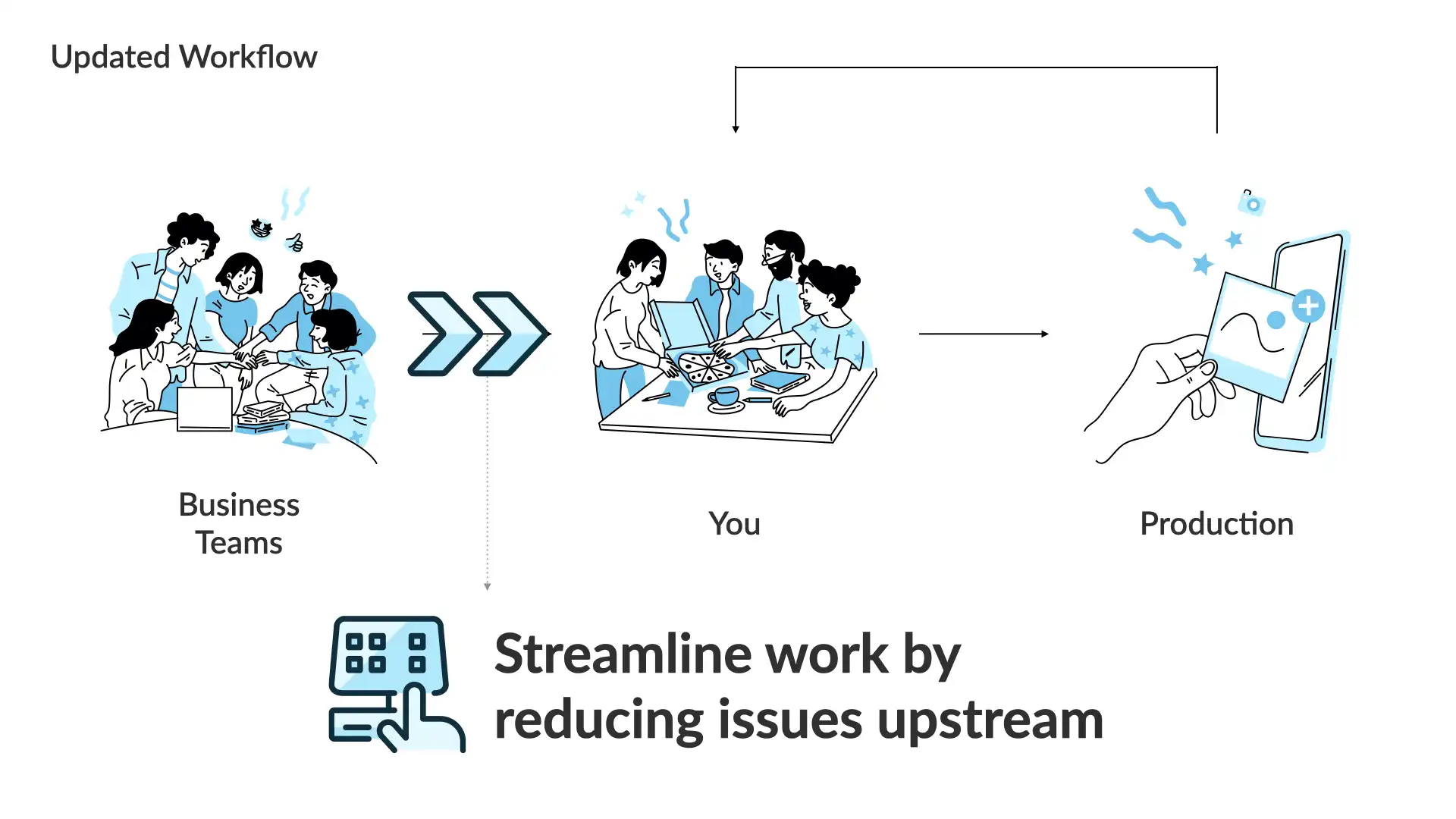

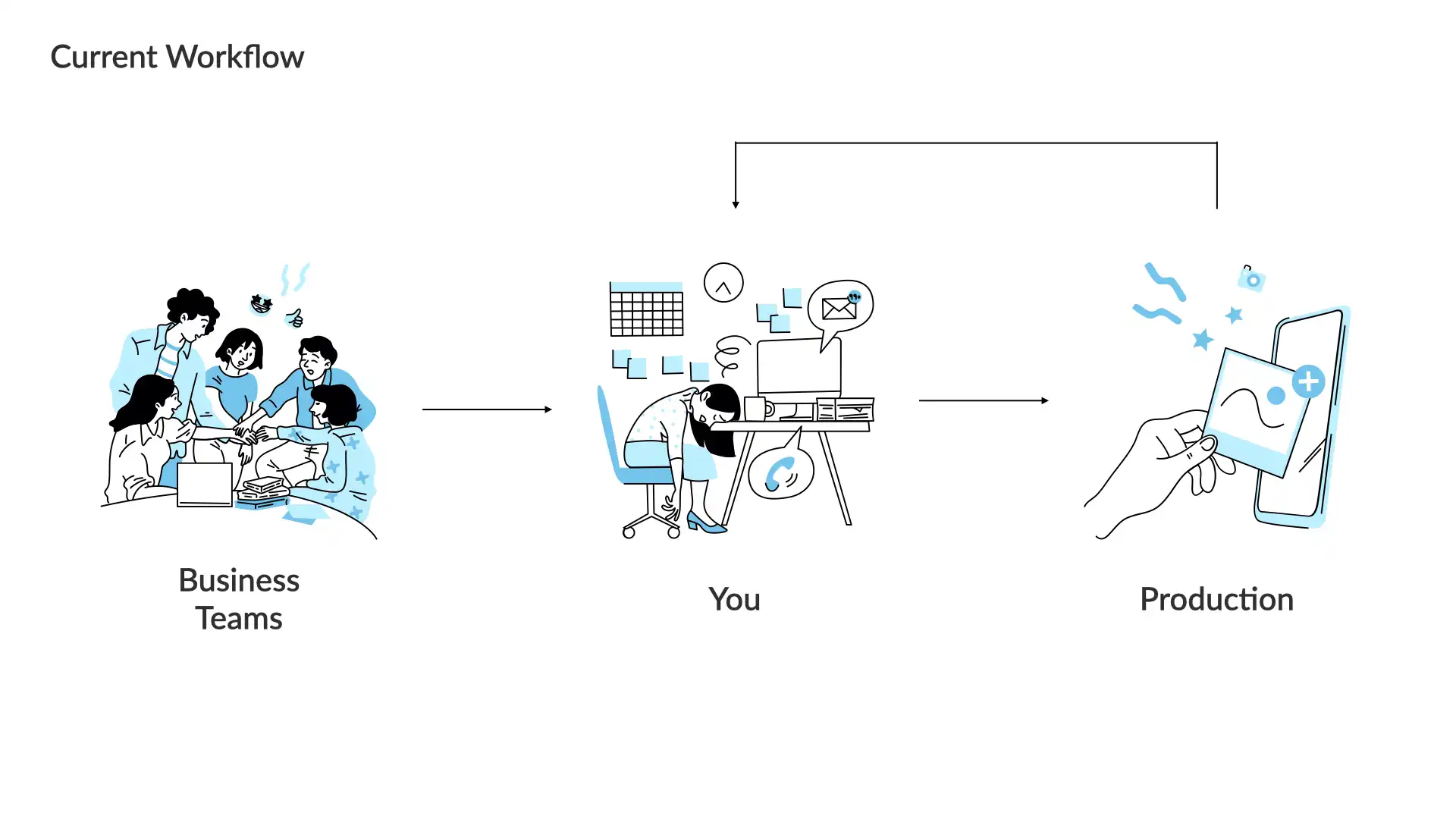

The current workflow for most security teams is simple.

A business team has built or bought something and they want to get it into production as quickly as possible. They do have business goals to meet after all.

You, the security person, is the gate they must pass before that happens.

This works-ish. Sadly, it leads to a lot of "hero" behaviour which prevents the actual challenge from being addressed and piles more pressure on the security team members.

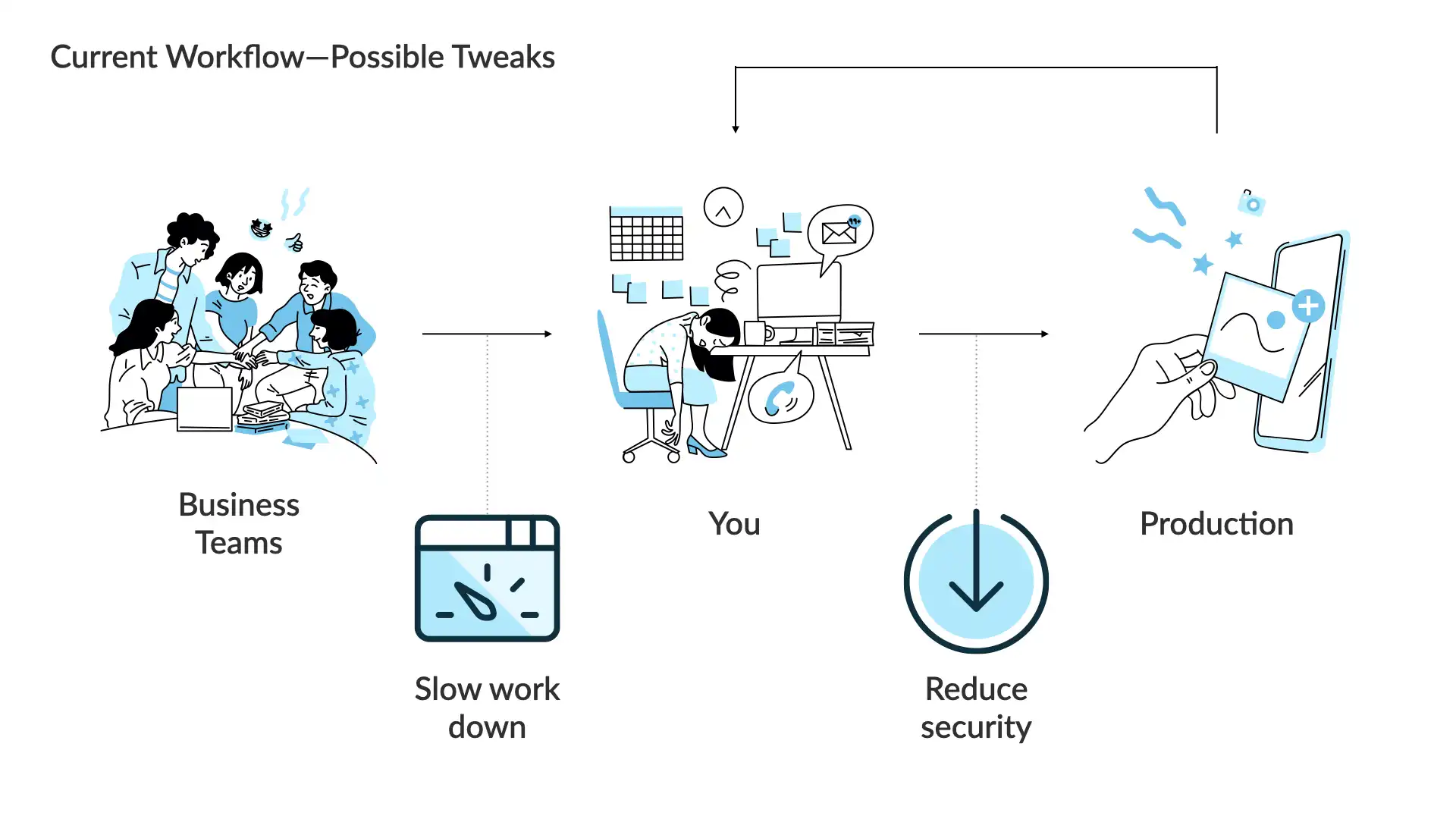

The fundamental challenge comes back to that ratio. There are a very limited number of security team members and way, way more business teams.

Security is almost always the slow down or roadblock for their productivity...even thought security is working at 100% or more of expected capacity.

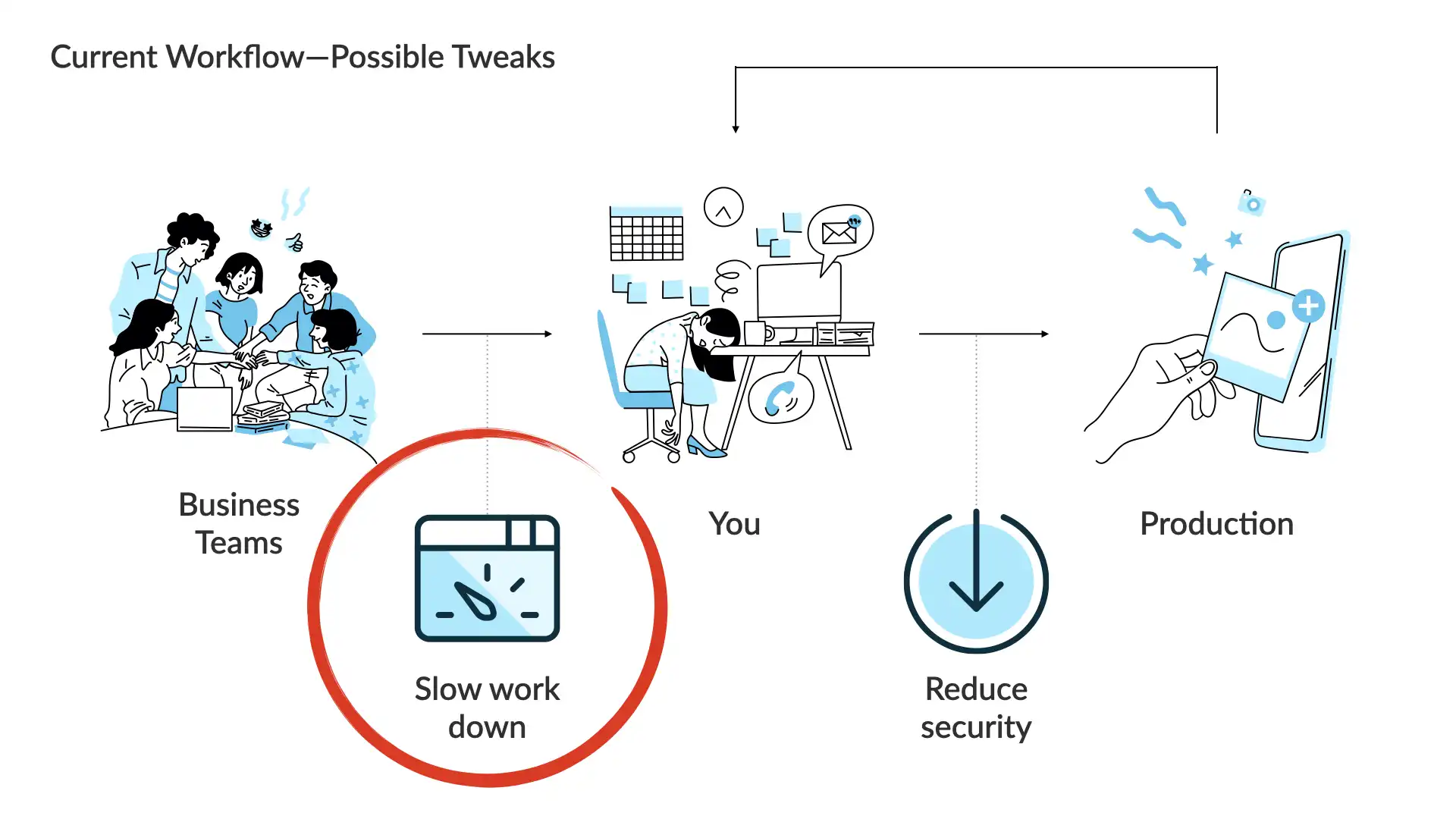

Keeping things at a high level, there are only 2 ways to smooth out this workflow.

You can slow down the incoming work.

or

You can reduce your security goals.

No security team should accept a reduced security posture as a matter of standard practice.

We need to continue to raise the strength and effectiveness of the security posture of our organizations.

We might be able to slow the incoming work down though...we're come back to that in a few.

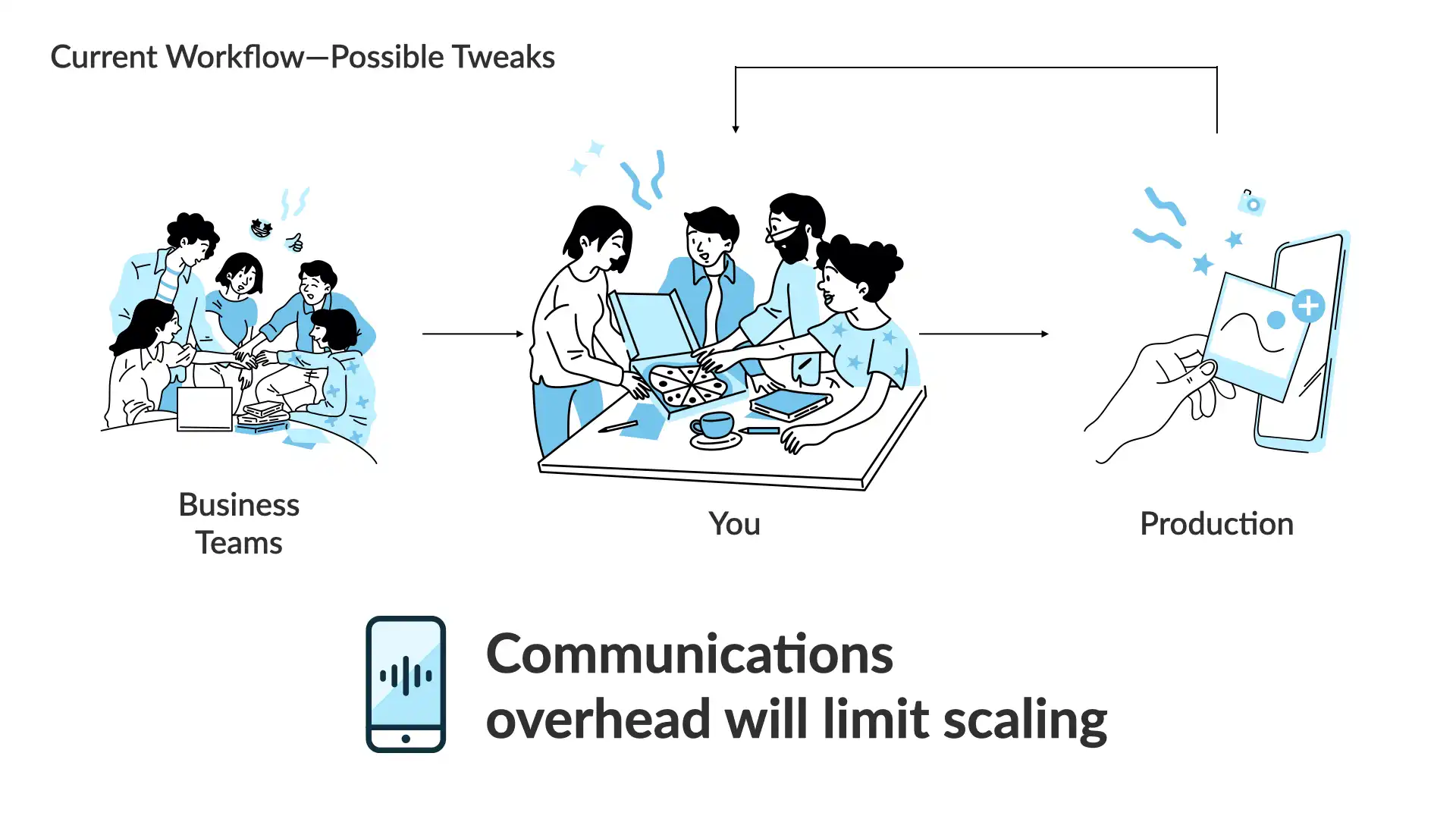

Now, you can add more folks to the security team. You can scale up the team to handle more work.

This can help.

But, hiring anyone is an ongoing expense (something about always wanted to be paid 😉) and it takes time for new team members to come up to speed.

And as we've already looked at, the ratio of security team members to the rest of the business is so disproportionate that it's unlikely you'd be able to get it down to anything reasonable to actually address these challenges.

This is not a path that will successfully solve this issue.

So, what approach will work?

We—the security team—need to work with our business teams to reduce the issues upstream.

We need less security issues coming to us before systems are rolled out to production.

How do we do that?

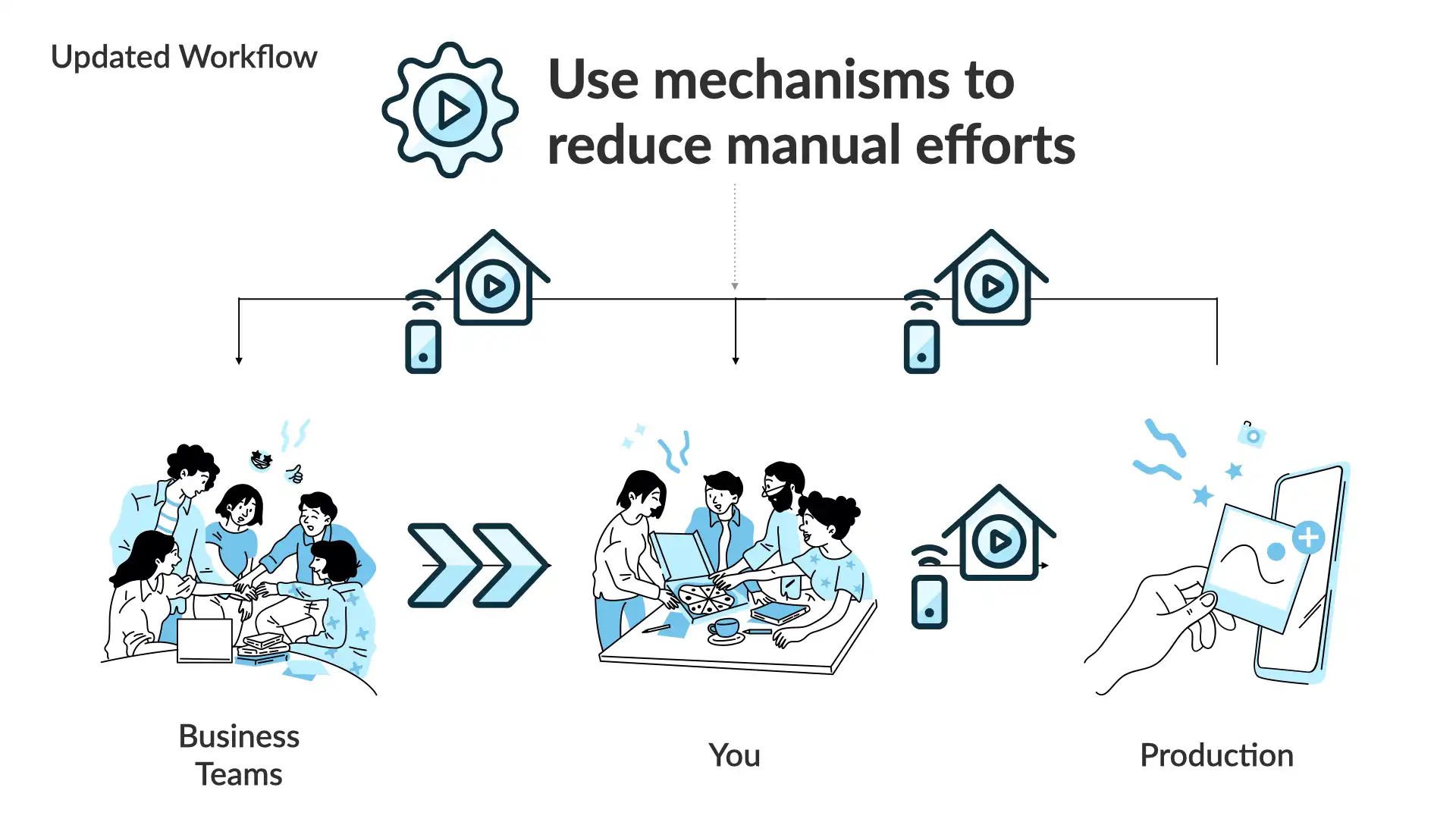

Our general approach will be to use mechanisms to reduce our manual efforts.

A mechanism (in this context) means that we're going to try and create a tool of some sort—a process, an automation, etc.—and get folks using it, all while making sure it's delivering what we actually want.

What we don't want is more process and red tape. If something isn't serving the business' end goals, get rid of it!

Mechanisms and automation

...sort of

There's a lot we could look at here, but for this talk, we're going to look at the communications side of things.

Can we change the way we communicate and reduce the amount of work our teams are receiving? Can we make it easier to communicate in a more productive way?

Yes, we usually lean into technology to solve problems. We eagerly roll out code and additional layers of systems to address issues as we come across them.

That's not necessarily a bad thing. But, more frequently that we'd like to admit, we just end up with more overhead and challenges that are harder to address because the systems we just deployed have added more constraints!

We're going to take a deeper look at a breach notification from here in Canada. Don't worry, this will be a positive example that we'll be examining to see if we can make some tweaks to improve it even further.

But let's start with a general template for a notification...

The formula for a breach notification—e.g. letting people know there was a security incident and they were affected—is very straightforward...at a high or conceptual level.

It is:

- What happened?

- What information was affected?

- What have we done in response to the breach?

- What does this mean for you?

- More information and how to make a compliant (with a regulator, etc.)

- Signed by a representative of the company

Remember, we're not trying to blame anyone. We're trying to learn!

We're going to dive into a breach TransLink had in 2020. TransLink is responsible for the regional transit network in metro Vancouver.

They were breached in 2020 and the entire recovery and review process took 7 months. That includes the clean up and work with the privacy regulator. The initial incident response appeared to be quite quick.

Overall, I think there communications were good. When compared to a lot of security comms, they probably should be seen as excellent.

But, I'm a bit picky and I think TransLink could've made a couple of small tweaks to really knock it out of the park.

From the TransLink primary web page for this incident:

"

In December 2020, TransLink was the victim of a cyberattack. Upon detection, we took immediate action to shut down multiple computer systems as a protective measure and launched an investigation.

Over the course of the investigation, we worked tirelessly with cybersecurity experts to understand what happened and determine what information was unlawfully accessed. We also worked with law enforcement authorities and notified the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for BC.

This investigation has been a complex and time-consuming process that took months to complete. It involved extensive analysis, the use of e-discovery tools, and manual data reviews.

The privacy review concluded in June 2021.

"

As you can see, that is a solid opening. However, it does fall into some very common traps. Let's make a couple of edits...

In December 2020, TransLink was the victim of a cyberattack. Upon detection, we took immediate action to shut down multiple computer systems as a protective measures and launched an investigation.

Over the course of the investigation, wWe worked tirelessly with cybersecurity experts to understand what happened and determine what information was unlawfully accessed. We also worked with law enforcement authorities and notified the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for BC.

Here is what you need to know about your information.

This investigation has been a complex and time-consuming process that took months to complete. It involved extensive analysis, the use of e-discovery tools, and manual data reviews.

The privacy review concluded in June 2021.

Why those changes?

The original was too complicated, not empathetic, and it didn't set a shared context.

The same changes we made shifted the opening to quickly state what had happened, hint at the scale of effort to respond, and then quickly dives into the number one thing the reader of the letter would want to know.

Of all the common traps the original fell into, the most egregious—yes, even in the context of a good communication, there can be things that are egregious!—is that it's written from what the organization wants you know about the situation, not what the reader wants or needs to know!

Yes, breach notifications and other security communications can be used to reduce damage to an organizations reputation. However, it's critical that you remember that both parties in this communication are victims.

The organization—TransLink in this case—was the victim of cybercrime. The intended reader of this letter were also victims of that same crime.

As long as the origination wasn't derelict in their care of the information, this post shouldn't be written with the tone of "it's not my fault!", but one that lands more along the lines of, "we are both impacted here, but let's start to fix this by focusing on you".

Let's go for a complete re-write. We'll start with a strong and direct opener written with the reader and their position in all of this top of mind.

"

In December 2020, TransLink was hacked. When we found this out, we worked as quickly as possible to protect your data.

"

Simple. Straight to the point. With the first sentence, the reader knows what this communication is about and what happened.

The second puts TransLink in a positive light and it's also—without all of the fancy terminology or long-winded explanation—an accurate description of what happened.

We continue...

"

We brought in cybersecurity experts to help. We also contacted law enforcement and the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for BC.

"

This next section is primarily a regulatory requirement. They need to let the reader know that they've complied with the local privacy legislation.

But, we frame it here as a follow-up to the statement about working as quickly as possible to protect your data.

This way, it shows—in plain language—the effort that the organization went to in response to the breach.

The next line is critical and it's often missing from these types of notifications.

"

We’ve contacted the people whose data was accessed during the hack to help them.

"

Remember, the original text that we're rewriting was published on the TransLink website. It went out to everyone. That makes sense due to the scale of the breach and the nature of the organization. This agency is the regional transit authority and its work impacts everyone in the area.

We add this line as a direct answer to the question in every readers mind, "Was my data breached?". This direct statement answers that near the top, helping the reader focus on the rest of the message.

We follow that up with an explanation of what the reader can find on this page.

"

This webpage contains information about what happened. It listed what data was accessed and what steps we’re taking to try and make sure this doesn’t happen again.

"

And finally, we closing this section with a catch-all to help answer any questions the reader may have after reading the rest of the page. This is may be implied, but by stating it, the reader is reminded of the dynamic and that organization is trying to help reduce the overall risk and any potential harms that may come from the breach.

"

If you have any questions after reading this information, we’ve set up a few different ways to get in touch with us directly. Those methods are listed at the bottom of this page.

"

Again, the communication from TransLink during this incident was great. But, with a few small tweaks, I think we've improved it to focus on what matters most to their target audience.

Our updated version heads off a lot of questions by answering them directly. We also reduced the complexity of the writing making the text easier to read. We've dropped the level equivalent from about 2nd year of University to middle school level (as per the Gunning fog index). That makes the entire text much more accessible.

This approach should reduce the number of inbound requests to the organization. And it's an approach you can use internally to do the same for your team.

Clear communication can reduce your workload.

Let's look at another positive example. This one is from CISA, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency in the US. CISA is the national coordinator for critical infrastructure and resilience in the United States and often acts as a cybersecurity centre of excellence for their public service.

We're going to dig into their Log4j vulnerability guidance page. They got this page up quickly when Log4j went public and used it as the single source of truth for the issue. They updated repeatedly with information about the vulnerability as it came to light and made sure that the page was as comprehensive as possible.

Here's a section of the CISA page that we'll be looking at. It's solid.

But, I do want to point out one approach that may create challenges for the intended audience...

Each of the highlighted passages are technical terms or industry specific language.

That's not necessarily a bad thing. CISA was a specific target audience in mind—security experts.

However, given their position within the US public service, they are also going to have a lot of general IT folks and other various interested folks reading this too.

The question is, can we reduce the specific language without reducing the effectiveness of the writing or the technical details?

We won't go through each term point by point, but here's a quick example of what we could swap out:

- "active, widespread exploitation" => "attackers are currently using this"

- "unauthenticated remote actor" => "attackers don't need to login to use this successfully over the internet"

Yes, sometimes a longer sentence is a clearer one. When in doubt, a longer sentence with less niche terms and more straightforward language is probably going to be more effective.

This also required more context. While this page is for a specific vulnerability, it has a wide ranging impact that is crying out for more context.

The second paragraph with, "...is very broadly used in a variety..." doesn't provide enough context. Something like this might've been more effective, "Log4j is a key building block of a lot of software and most people are unaware their systems are using it. It helps developers write log information that's helpful for troubleshooting, that's why it is a part of a lot of unexpected systems."

Last example, again a positive one.

This time, we'll look at an open source project called Prowler. This is "an open-source security tool designed to assess and enforce security best practices across AWS, Azure, Google Cloud, and Kubernetes".

It's a great project and helps a lot of organizations improve their security posture.

In this example, we're going to look a specific detection from the platform and how it aims to help developers and security folks avoid a security issue.

Here's the detection information in full. It's typically delivered as a JSON object in the platform or teams will route these to Slack or some other system where they are typically working.

This is a solid detection. The description is crystal clear. The risk is well constructed and the recommendation isn't too bad.

But two things jump out at me here.

The first is the opening sentence of the risk, "The use of a hard-coded password increases the possibility of password guessing." That doesn't accurately convey the level of risk.

How much does this increase the possibility of the password being guessed? Is that actually the case with this detection? Why is this worth the time to fix?

The second challenge is the recommended fix. Sure, AWS Secrets Manager could help address the issue. But are there other approaches that would work here? Are there other secrets managers that would work?

Again, the original is solid.

But if it provided more of the why in the risk it would be more useful.

"Hard-coded passwords can be stolen by attackers or accidentally exposed in a source code repository. Avoid this pattern if at all possible, as attackers can easily compromise the account the password has access to."

Similarly, the recommendation can be expanded to help the recipient find the best solution for their situation.

"Using a tool to manage secrets—like AWS Secrets Manager—keeps passwords and other secrets out of your code. This partner makes it easier to update that information (e.g., change the password), while keeping it more secure as the function requests the password only when it's needed."

A couple small adjustments and we've reduce the dots the recipient is required to connect!

As we've seen in the examples we've discussion—and again, they are all positive examples!

We can make some small adjustments to our approach to communication to help everyone make better security decisions and help reduce the incoming requests to our team.

For communications:

- Keep it simple

- Focus on the reader

- Create shared context

- Be empathetic

Working upstream

We've talked about communications with an eye to how clearer communications can reduce incoming requests to your security team.

We're going to take that a step further and talk about education. One gap most security teams have today is a failure to help the rest of the business understand how to prevent security issues.

I'm not talking about security awareness training (don't even get me started on that) or a patch management process. I'm talking about genuinely investing the time required to help other folks outside of the security team understand how security first thinking can help them.

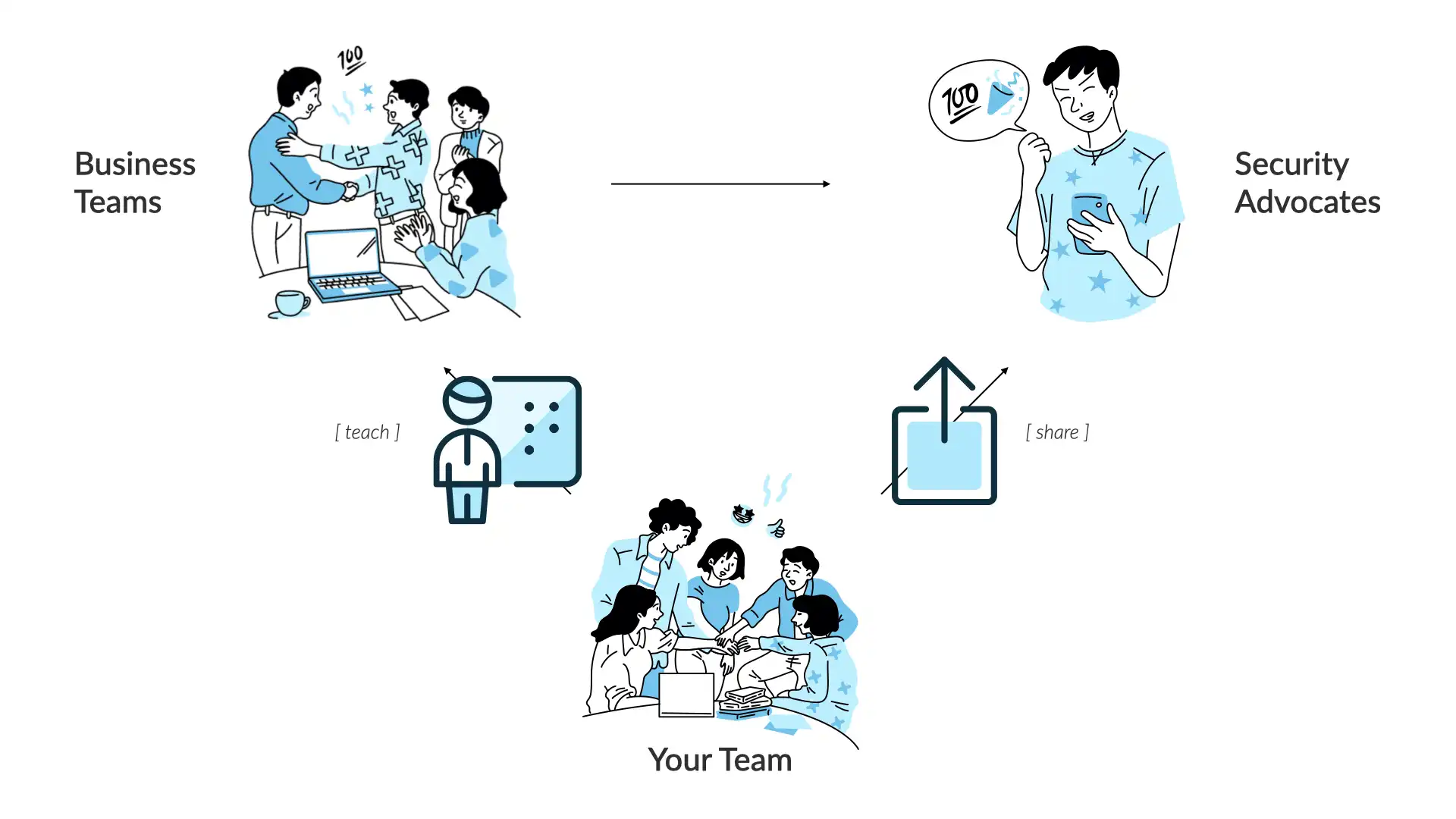

Your team works regularly with a number of business teams.

As we discussed in the intro for this talk, that ratio is heavily weighted towards the business teams. You can't keep up with the work coming from all of the different business teams.

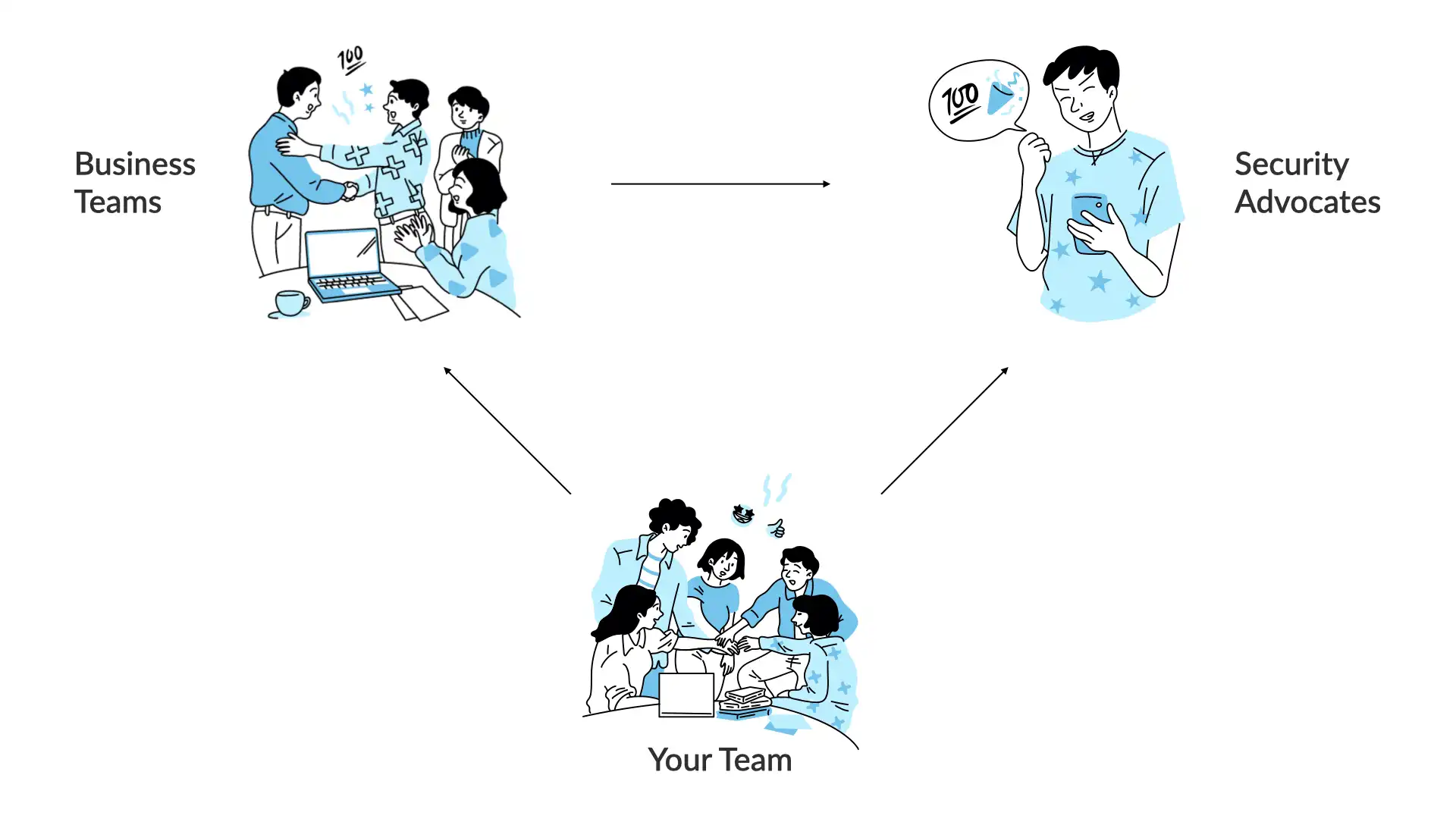

One way to help with this is to recruit other folks within the organization to advocate for more security-first or security-focused decisions.

Programs that help build this type of internal community go by a few different names—Security Champions, Security Guardians, etc.—for simplicity we'll call them "Security Advocates". Folks in this group—either "officially" recognized or not, are the people that other teams lean on for security help.

Most organizations have folks filling these types of roles for a variety of specializations. Whether it's usability, performance, accessibility, a specific framework, data analysis, etc., there's always that "go-to" for a certain topic.

Even when you don't have a specific program to nurture and expand this community, this type of dynamic still manages to surface. Making it an actual recognized effort has a lot of benefit. The foremost being you can track your efforts and invest (time, money, etc.) where it's having the biggest impact.

Once you've identified these folks, you can start to shift the dynamic between your team and the business teams.

Even if you don't identify these advocates, you should try to shift the dynamic between the security team and the business teams.

Your goal as a security team should be to try and teach the business teams about security as often as possible. With few exceptions, you should try to evolve your current workflows to try and move as much of that work to the business teams as possible.

Now, I know what you're thinking. Why would other teams take on our work? Why do would we want to cede these responsibilities to those teams, what are we supposed to do?

For your work, don't worry. There is and will always be more than enough security work to go around. 🤦

For the business teams, the advantage is easy to understand. They are best positioned to understand the full context of the risk decision (what are the risks of this new feature/solution/product?) and understanding how security can help them meet their business goals, helps them to make better decisions. That improvement helps reduce the time it takes to get things out the door and meet their goals more quickly.

Remember, this is not a complete move of security decisions to the business team. The goal of this effort is to move the decisions that are best made by an informed and educated business team to that team. The security team should be contributing to organization-wide challenges and cross-team risks.

As these efforts mature, your team will do less teaching and more sharing with teh security advocates. They in turn will take on more of the teaching role.

This can happen organically. But in each case where I've seen this type of effort succeed, it's been through a well understood and funded program.

That can mean any number of things, but it's common to have some sort of incentive structure for the advocates. Whether that's perks or specific compensation rewards or a faster path to advancement. Find what works for your organization's culture and make sure that this type of program is set up so that everyone involved sees the benefit.

You may see this and think it'll never work for your organization. Business teams don't care enough about security to give it this type of prioritization. The cooperation you see today is only because teams have to deal with security (whether by regulation or policy).

When I've discussed that idea with executives around the world, I see a common problem. Most people think of security as work to stop bad things from happening. While that's part of it, that's only a fraction of the work under the security umbrella.

The goal of security is simple. It's to make sure that what you build works as intended...and only as intended.

That's a positive goal. Stopping bad things is a negative goal and it's impossible to actually track that. The positive goal is easier to get people to rally around.

When you understand that security is trying to make sure that the work a team is doing works and only does what it's supposed to, now everyone understands they are working towards the same goal!

Security and the business have the same goals.

They all want:

- Low-risk changes to production

- Resilient systems

- Visibility into their data and the processes they use

To meet those goals, you need to provide the why.

Why does this request matter? Why is this risk an issue?

If you help people understand the why, they can make better decisions moving forward. We want people to think through each situation that comes up. Technology is too complicated to map out each potential challenger beforehand.

If people understand the context of a requirement, they can make better decisions. As the expert, it's up to you to provide that understanding.

Remember, that you are the security expert. No one shared your context. You have a broad understanding of the thread landscape, the controls within your organization, and the overall risks the business is trying to balance.

The business teams are just trying to get their work done! They have goals they are working towards and are trying to navigate the various systems and processes to the best of their abilities. They are experts in something else entirely and should not be expected to be or become security experts.

Your goal is to make security frictionless. Or maybe a better call out is your goal is to use fiction judicious, helping other people make better decisions.

How can you start? Here are a few ideas for some simple techniques to get the ball rolling:

- Open office hours

- Review design docs and ask questions

- Record quick video explainers for security questions

- Join team channels and learn!

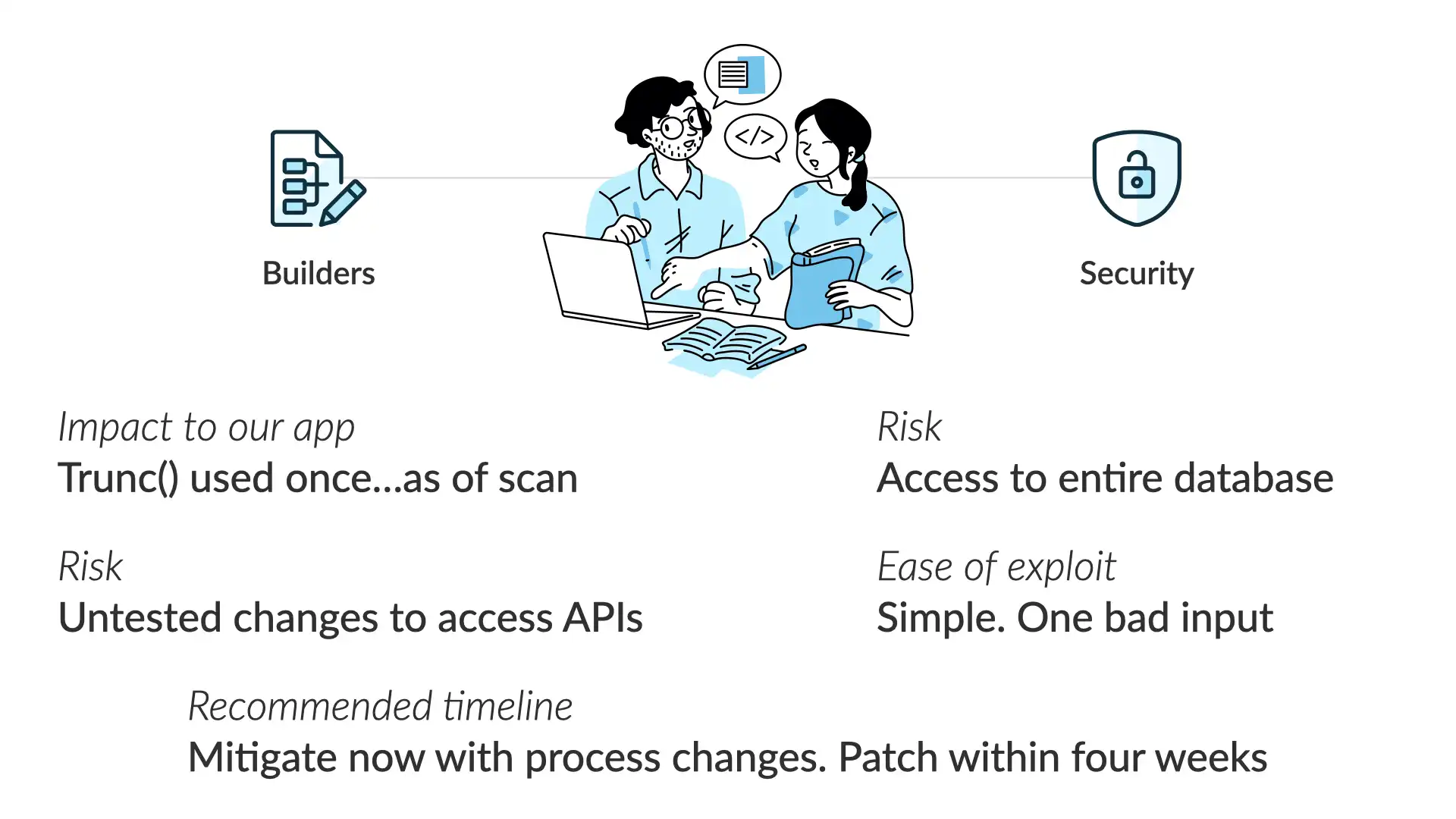

Let's a take look a how the business team and the security team approach the same issue.

There was a vulnerability in the popular django python framework in 2022. This framework is used to help build web apps and APIs. The vulnerability was an SQL injection—sending bad database requests to generate unexpected results—that could expose data that shouldn't be available.

This was an important issue to fix, but not an emergency. Think weeks, not days.

If we put on our security hat, we see that...

Risk

Exfiltration of all data in connected database

Ease of exploit

Simple. Crafted string input will start attack

Recommendation

Patch all instances of django with available patch to address issues

Likelihood of exploit

???

Recommended timeline

As soon as possible

With our builder/business had on...

Risk

Attackers get all of the data in the django database

Functions impacted

Trunc() & Extract()

Issue

Trunc(kind) & Extract(lookup_name) fail to properly sanitize input

Impact to our app

One use of Trunc() in codebase currently

Recommended timelines

Low priority. Combine with future djano updates

If we line up these perspectives—by working together as we've discussed—here's where we end up:

Impact to our app

Trunc() used once...as of our last code scan

Risk

Access to the entire database

Risk of the fix

Untested changes to access APIs

East of exploit

Simple. One bad input

Recommended timelines

Mitigate now with process changes. Patch within four weeks

Keys

Remember, most security teams are feeling the crunch. They are overloaded and under budget pressures.

A lot of that has to do with the fact that a small number of security professionals are accountable for the security of a large number of business teams!

Often security is blocking other work and tries to work harder to solve the problem.

Focus on building out mechanisms that help reduce the manual effort required to do any security work.

However, focusing first on clear communications can help free up resources because you're helping everyone in the organization to better understand security and specific issues without fielding individual questions.

Streamline the work your team does receive by aiming to reduce issues upstream. By education business teams so that they can make stronger security decisions, you'll reduce what falls to your team to handle.

Communicate

- Keep it simple

- Focus on the audience

- Create shared context

- Be empathetic

Educate

- Provide the why

- Security is one priority

- You have the same goals

- Be empathetic